Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers

-

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

By definition, though, that makes it not a container in those cases, but a Type 2 hypervisor. And what a bad idea that is. Now we are just automated VirtualBox.

Containers require a shared kernel to be a container. It's the shared kernel that gives the behaviour and performance that makes it interesting. Without that, it's just misleading and crappy.

It is in no way a type 2 hypervisor at this point. OpenShift (Docker) running on physical systems that spin up VMs on hardware. No type 2 anywhere.

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

Go statically links the compiled code. Same source code is compiled for Linux or Windows or Mac or BSD. You're making my point with the first statement. There are no kernel dependencies, external libraries, etc with a Go app in the container. The same source could be run across most operating systems (excluding AIX and some other UNIX).

-

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

By definition, though, that makes it not a container in those cases, but a Type 2 hypervisor. And what a bad idea that is. Now we are just automated VirtualBox.

Containers require a shared kernel to be a container. It's the shared kernel that gives the behaviour and performance that makes it interesting. Without that, it's just misleading and crappy.

It is in no way a type 2 hypervisor at this point. OpenShift (Docker) running on physical systems that spin up VMs on hardware. No type 2 anywhere.

A full VM would require a Type 2. The description you gave was of a Type 2, not a Container. If it loads a full VM (including a kernel), it's a Type 2.

It has to be one or the other.

If it doesn't, then it's the shared kernel I mentioned.

-

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

Go statically links the compiled code. Same source code is compiled for Linux or Windows or Mac or BSD. You're making my point with the first statement. There are no kernel dependencies, external libraries, etc with a Go app in the container. The same source could be run across most operating systems (excluding AIX and some other UNIX).

But your point was that Docker was including a kernel to run a full VM. My point was that it doesn't have to, it uses a shared kernel. So this makes my point, that Go doesn't require a full VM, therefore can use whatever kernel is already there. So it is a shared kernel.

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

By definition, though, that makes it not a container in those cases, but a Type 2 hypervisor. And what a bad idea that is. Now we are just automated VirtualBox.

Containers require a shared kernel to be a container. It's the shared kernel that gives the behaviour and performance that makes it interesting. Without that, it's just misleading and crappy.

It is in no way a type 2 hypervisor at this point. OpenShift (Docker) running on physical systems that spin up VMs on hardware. No type 2 anywhere.

A full VM would require a Type 2. The description you gave was of a Type 2, not a Container. If it loads a full VM (including a kernel), it's a Type 2.

It has to be one or the other.

That sentence makes no sense. It's a VM running on bare metal. There is no type 2 anywhere.

And even if it was, that really has no bearing on anything anyway.

-

If DevOps is not Job Title, but how the hell I am DevOps Engineer

(Recent change thus the whole dive into all of this.) -

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

By definition, though, that makes it not a container in those cases, but a Type 2 hypervisor. And what a bad idea that is. Now we are just automated VirtualBox.

Containers require a shared kernel to be a container. It's the shared kernel that gives the behaviour and performance that makes it interesting. Without that, it's just misleading and crappy.

It is in no way a type 2 hypervisor at this point. OpenShift (Docker) running on physical systems that spin up VMs on hardware. No type 2 anywhere.

A full VM would require a Type 2. The description you gave was of a Type 2, not a Container. If it loads a full VM (including a kernel), it's a Type 2.

It has to be one or the other.

That sentence makes no sense. It's a VM running on bare metal. There is no type 2 anywhere.

VM on bare metal isnt' a thing. You described Docker as a Type 2 hypervisor. By your description, Docker is the type 2 hypervisor, rather than being containerization.

There's no other option. If it can run a full VM, only a Type 2 can do that on top of an OS. Containers can't do that, by definition.

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

Go statically links the compiled code. Same source code is compiled for Linux or Windows or Mac or BSD. You're making my point with the first statement. There are no kernel dependencies, external libraries, etc with a Go app in the container. The same source could be run across most operating systems (excluding AIX and some other UNIX).

But your point was that Docker was including a kernel to run a full VM. My point was that it doesn't have to, it uses a shared kernel. So this makes my point, that Go doesn't require a full VM, therefore can use whatever kernel is already there. So it is a shared kernel.

OMG. It was not. My point is you can run Docker containers with NO SHARED KERNEL.

There were two different ideas in that paragraph. One was you can run Go containers with no shared kernel. The other was an example of how Red Hat is using Docker without a shared kernel.

-

@emad-r said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

If DevOps is not Job Title, but how the hell I am DevOps Engineer

(Recent change thus the whole dive into all of this.)DevOps is a department, DevOps Admin is a job title. Like System Administration isn't a title, but System Administrator is.

DevOps is a subset of System Administration.

-

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

Go statically links the compiled code. Same source code is compiled for Linux or Windows or Mac or BSD. You're making my point with the first statement. There are no kernel dependencies, external libraries, etc with a Go app in the container. The same source could be run across most operating systems (excluding AIX and some other UNIX).

But your point was that Docker was including a kernel to run a full VM. My point was that it doesn't have to, it uses a shared kernel. So this makes my point, that Go doesn't require a full VM, therefore can use whatever kernel is already there. So it is a shared kernel.

OMG. It was not. My point is you can run Docker containers with NO SHARED KERNEL.

Right, so Docker is a type 2 hypervisor.

If you believe this statement is wrong, please explain how? Because to me, you just screamed "DOCKER IS A TYPE 2 HYPERVISOR" while seemingly trying to say it is not.

Shared Kernel = Contrainerization

No Shared Kernel = Type 2 Hypervisor (when an OS is needed beneath, like with Docker.) -

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

There were two different ideas in that paragraph. One was you can run Go containers with no shared kernel. The other was an example of how Red Hat is using Docker without a shared kernel.

I get that. Go doesn't required a shared kernel, or anything. So Go isn't relevant to the other discussion. Go being able to be used anywhere doesn't tell us anything about the thing that it is running on.

If RH is able to run Docker without a shared kernel, that by definition means Docker is a Type 2 hypervisor if that is actually true.

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

Go statically links the compiled code. Same source code is compiled for Linux or Windows or Mac or BSD. You're making my point with the first statement. There are no kernel dependencies, external libraries, etc with a Go app in the container. The same source could be run across most operating systems (excluding AIX and some other UNIX).

But your point was that Docker was including a kernel to run a full VM. My point was that it doesn't have to, it uses a shared kernel. So this makes my point, that Go doesn't require a full VM, therefore can use whatever kernel is already there. So it is a shared kernel.

OMG. It was not. My point is you can run Docker containers with NO SHARED KERNEL.

Right, so Docker is a type 2 hypervisor.

If you believe this statement is wrong, please explain how? Because to me, you just screamed "DOCKER IS A TYPE 2 HYPERVISOR" while seemingly trying to say it is not.

Shared Kernel = Contrainerization

No Shared Kernel = Type 2 Hypervisor (when an OS is needed beneath, like with Docker.)You're being purposefully obtuse. Your last sentence would mean KVM is a type 2. Docker creates a KVM VM on bare metal, type 1 end of story.

-

Just to be clear, that you claim Docker is a type 2 hypervisor does not prevent it from being a container technology at other times. Only that it is like ProxMox and can do two unrelated things.

ProxMox isn't virtualization itself, of course, but merges KVM and OpenVZ. Docker must be doing something similar, but with the Type 2 and the container stuff both built in under a single brand name.

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Just to be clear, that you claim Docker is a type 2 hypervisor does not prevent it from being a container technology at other times. Only that it is like ProxMox and can do two unrelated things.

ProxMox isn't virtualization itself, of course, but merges KVM and OpenVZ. Docker must be doing something similar, but with the Type 2 and the container stuff both built in under a single brand name.

I don't claim that and never have.

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r actually The main benefit of containers is to disconnect sysadmin and devel work.

Not really. Containers are virtualization like any other, they've been around for decades and the idea that they were anything for developers is an extremely recent use case of only a very specific subset of containers. Most containers, and most of the history of containers, don't do anything like that, no more than any other kind of virtualization.

Yes but I think here we are talking docker. Docker is like python virtual envs for anything and not just for python. This is their main meaning to me.

Sure, if we are talking Docker and not talking Containerization, then Docker just seems like a sloppy, error prone way to do that.

My biggest issue with Docker is that it seems to make things worse rather than better. More complexity, more things to break, more dependencies. It introduces the very problems it claims to solve, problems that we weren't experiencing previously.

It does that, it does create more complexity at first.

Installing an app for us is much easier, like PHP-FPM + apache, it is only 10 commands or something, however if you did in docker/container in VPS you get the extra benefit of having clean environment in the host OS always + the container can be moved around easily to another VPS + it is much easier for non smart people to get your app and its updates + Docker provides free accout to publish one app.

That's a theory, but in the real world I've seen the opposite. Docker requires too much knowledge and skill on both ends and isn't as portable as people say. Docker requires both the admins and the developers to do more work and if either gets it wrong, Docker is harder to deal with. And since you rarely control both sides, it's a pretty big problem.

Docker doesn't really give the benefits you list. It can do that, but so can more traditional containers, without all of the Docker problems.

So given that moving workloads, and containerizing aren't benefits to Docker (it does them, but it's not unique), what problem do you feel Docker is actually solving over older, simpler solutions?

If there is one thing Docker doesn't do, it's make things easier for non-smart people. It requires all people to be smarter. This is exactly the opposite of the value it is providing.

It does make software installs on remote location very easy man.

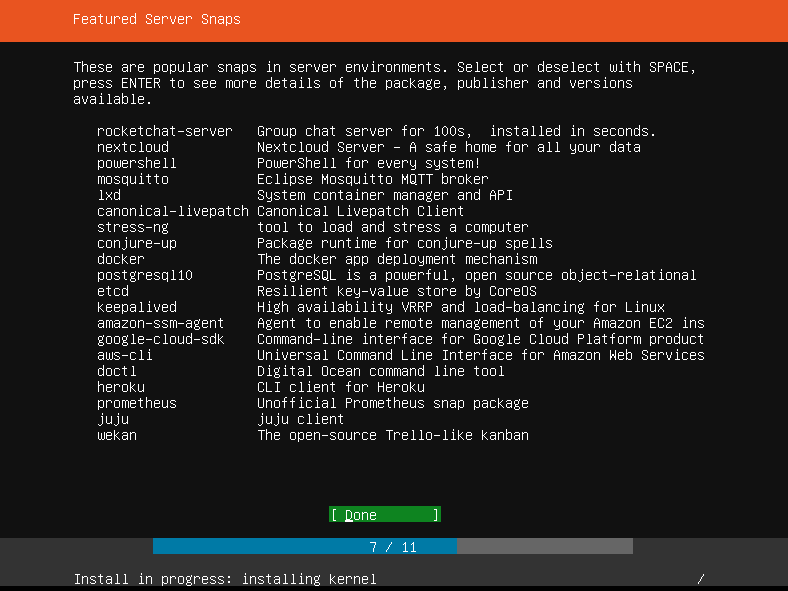

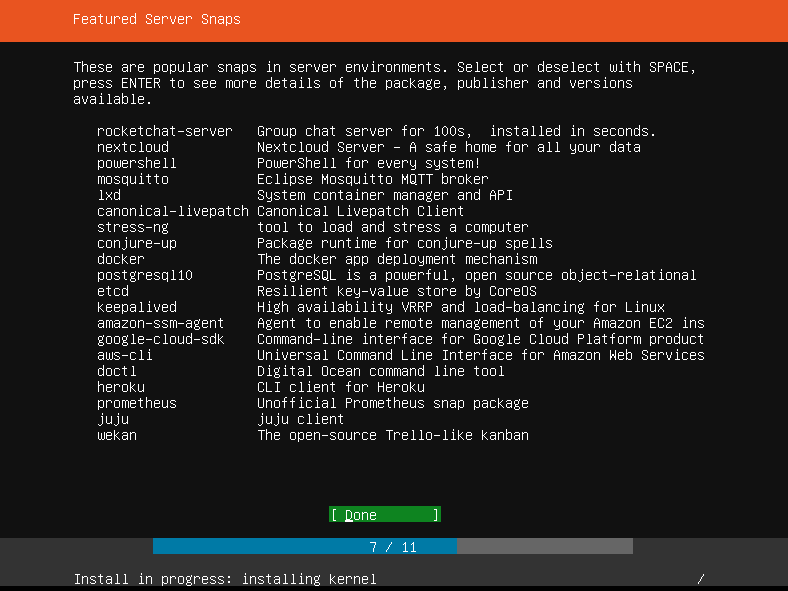

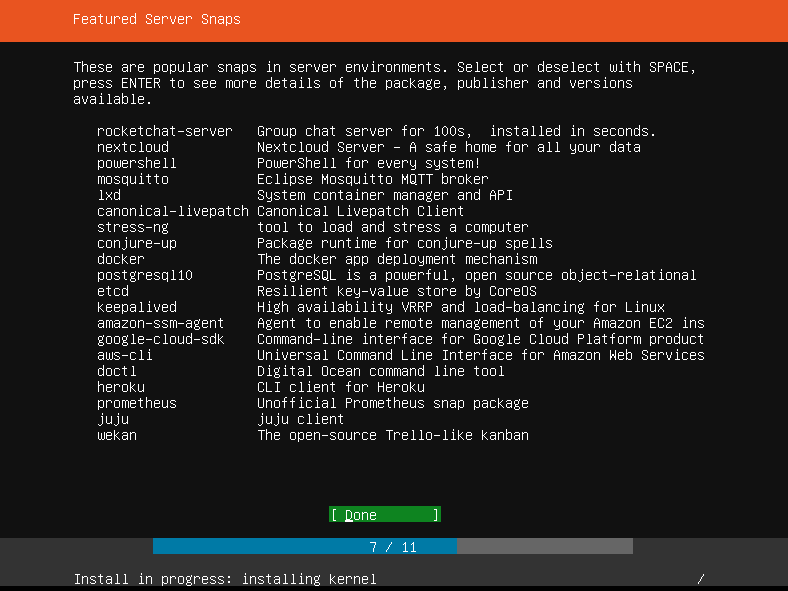

Ubuntu new installer, actually lists docker in the Ubuntu SErver install wizard, so you can easily tell an IT officer to

Load the ISO , tick this this this and bam you get ubuntu installed with docker.

However the way that Ubuntu installs Docker is abit Microsoftish as it installs it as SNAP to promote there SNAPs being able to manage anything which is like running a fork of fork, but the point is it gets installed and then theorically the IT officer in that remote location just types

docker pull YOUR SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT COMPANY

it is much easier said than done.

-

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Containers use shared kernels by definition, that's what makes it a container.

This isn't really how Docker works. Docker manages namespaces. If you use "FROM Alpine" then it will share the kernel, but if you write an app in Go and use "FROM scratch" it has zero reliance on a specific kernel. You can also run full VMs in a Docker container which is how Red Hat uses OpenShift to deploy OpenStack VMs.

Well go requires the kernel too. But yes for the most is the "from scratch" part which allows more abstraction

Well I mean you have to have a kernel for anything to run. My point was it is technically possible to run a Go app in Docker natively on Windows with no Linux anywhere.

Well sure, but you have a Windows kernel. Why would a Linux kernel be expected to be required to run a Go app? The Windows kernel has a Linux compatibility layer to mimic Linux calls. So we'd expect it to be able to run anything that can run on Linux.

I assume you are using Go as an example because normally you need to compile Go to the platform and if you compile against Linux, then Windows would not be able to run it? But is Docker handling the translation here, or is Windows? What if you ran it on BSD? Or a different architecture, like ARM?

Go statically links the compiled code. Same source code is compiled for Linux or Windows or Mac or BSD. You're making my point with the first statement. There are no kernel dependencies, external libraries, etc with a Go app in the container. The same source could be run across most operating systems (excluding AIX and some other UNIX).

But your point was that Docker was including a kernel to run a full VM. My point was that it doesn't have to, it uses a shared kernel. So this makes my point, that Go doesn't require a full VM, therefore can use whatever kernel is already there. So it is a shared kernel.

OMG. It was not. My point is you can run Docker containers with NO SHARED KERNEL.

Right, so Docker is a type 2 hypervisor.

If you believe this statement is wrong, please explain how? Because to me, you just screamed "DOCKER IS A TYPE 2 HYPERVISOR" while seemingly trying to say it is not.

Shared Kernel = Contrainerization

No Shared Kernel = Type 2 Hypervisor (when an OS is needed beneath, like with Docker.)You're being purposefully obtuse. Your last sentence would mean KVM is a type 2. Docker creates a KVM VM on bare metal, type 1 end of story.

No, I'm not being obtuse at all. KVM doesn't run ON an OS, it IS the OS, making it a TYpe 1 (or Type 0 some call it.) We've covered this a lot and is unrelated here.

Docker is using KVM? So Socker is EXACTLY like ProxMox now? Just using Docker as the container and KVM for the virtualization? So Docker is NOT able to do full VMs, but just provides an interface to a hypervisor?

That's not at all the same as what you had said, that Docker was doing it itself. Any tool can automate something that already exists. I can write a script to manage KVM, it doesn't make the resulting VMs a script, or part of my script. It's just a management tool to the real thing.

It was obtuse to say it like Docker had this power and was doing things itself. Docker runs on top of an OS, so if Docker itself is virtualizing a full VM by definition it is a type 2. If Docker requires KVM, it can be a management tool for a type 1.

-

@stacksofplates said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

Just to be clear, that you claim Docker is a type 2 hypervisor does not prevent it from being a container technology at other times. Only that it is like ProxMox and can do two unrelated things.

ProxMox isn't virtualization itself, of course, but merges KVM and OpenVZ. Docker must be doing something similar, but with the Type 2 and the container stuff both built in under a single brand name.

I don't claim that and never have.

You stated it more than once when you said "Docker could run a full VM, no shared kernel", that's explaining that it is a type 2 no way around it. That's EXACTLY what a type 2 is.

But now you are saying that isn't what it does, that actually KVM is running it and Docker is still a container running on top of the OS. That's completely different than the original statement in every way.

-

@emad-r said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r actually The main benefit of containers is to disconnect sysadmin and devel work.

Not really. Containers are virtualization like any other, they've been around for decades and the idea that they were anything for developers is an extremely recent use case of only a very specific subset of containers. Most containers, and most of the history of containers, don't do anything like that, no more than any other kind of virtualization.

Yes but I think here we are talking docker. Docker is like python virtual envs for anything and not just for python. This is their main meaning to me.

Sure, if we are talking Docker and not talking Containerization, then Docker just seems like a sloppy, error prone way to do that.

My biggest issue with Docker is that it seems to make things worse rather than better. More complexity, more things to break, more dependencies. It introduces the very problems it claims to solve, problems that we weren't experiencing previously.

It does that, it does create more complexity at first.

Installing an app for us is much easier, like PHP-FPM + apache, it is only 10 commands or something, however if you did in docker/container in VPS you get the extra benefit of having clean environment in the host OS always + the container can be moved around easily to another VPS + it is much easier for non smart people to get your app and its updates + Docker provides free accout to publish one app.

That's a theory, but in the real world I've seen the opposite. Docker requires too much knowledge and skill on both ends and isn't as portable as people say. Docker requires both the admins and the developers to do more work and if either gets it wrong, Docker is harder to deal with. And since you rarely control both sides, it's a pretty big problem.

Docker doesn't really give the benefits you list. It can do that, but so can more traditional containers, without all of the Docker problems.

So given that moving workloads, and containerizing aren't benefits to Docker (it does them, but it's not unique), what problem do you feel Docker is actually solving over older, simpler solutions?

If there is one thing Docker doesn't do, it's make things easier for non-smart people. It requires all people to be smarter. This is exactly the opposite of the value it is providing.

It does make software installs on remote location very easy man.

Ubuntu new installer, actually lists docker in the Ubuntu SErver install wizard, so you can easily tell an IT officer to

Load the ISO , tick this this this and bam you get ubuntu installed with docker.

However the way that Ubuntu installs Docker is abit Microsoftish as it installs it as SNAP to promote there SNAPs being able to manage anything which is like running a fork of fork, but the point is it gets installed and then theorically the IT officer in that remote location just types

docker pull YOUR SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT COMPANY

it is much easier said than done.

Why use Docker when you could just use Snaps directly?

-

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@scottalanmiller said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@matteo-nunziati said in Check my 2 min audio theory on Containers:

@emad-r actually The main benefit of containers is to disconnect sysadmin and devel work.

Not really. Containers are virtualization like any other, they've been around for decades and the idea that they were anything for developers is an extremely recent use case of only a very specific subset of containers. Most containers, and most of the history of containers, don't do anything like that, no more than any other kind of virtualization.

Yes but I think here we are talking docker. Docker is like python virtual envs for anything and not just for python. This is their main meaning to me.

Sure, if we are talking Docker and not talking Containerization, then Docker just seems like a sloppy, error prone way to do that.

My biggest issue with Docker is that it seems to make things worse rather than better. More complexity, more things to break, more dependencies. It introduces the very problems it claims to solve, problems that we weren't experiencing previously.

It does that, it does create more complexity at first.

Installing an app for us is much easier, like PHP-FPM + apache, it is only 10 commands or something, however if you did in docker/container in VPS you get the extra benefit of having clean environment in the host OS always + the container can be moved around easily to another VPS + it is much easier for non smart people to get your app and its updates + Docker provides free accout to publish one app.

That's a theory, but in the real world I've seen the opposite. Docker requires too much knowledge and skill on both ends and isn't as portable as people say. Docker requires both the admins and the developers to do more work and if either gets it wrong, Docker is harder to deal with. And since you rarely control both sides, it's a pretty big problem.

Docker doesn't really give the benefits you list. It can do that, but so can more traditional containers, without all of the Docker problems.

So given that moving workloads, and containerizing aren't benefits to Docker (it does them, but it's not unique), what problem do you feel Docker is actually solving over older, simpler solutions?

If there is one thing Docker doesn't do, it's make things easier for non-smart people. It requires all people to be smarter. This is exactly the opposite of the value it is providing.

It does make software installs on remote location very easy man.

Ubuntu new installer, actually lists docker in the Ubuntu SErver install wizard, so you can easily tell an IT officer to

Load the ISO , tick this this this and bam you get ubuntu installed with docker.

However the way that Ubuntu installs Docker is abit Microsoftish as it installs it as SNAP to promote there SNAPs being able to manage anything which is like running a fork of fork, but the point is it gets installed and then theorically the IT officer in that remote location just types

docker pull YOUR SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT COMPANY

it is much easier said than done.

Why use Docker when you could just use Snaps directly?

Cause you dont know much about it and you use Docker cause it is the most known.

But how can I get survey of the most used tools in this early stage, like we all know that in Hypervisor world it goes like this

- VMware ESXi

- KVM and Hyper-V

So people that dont know much will always choose ESXi

I would love to know how much OpenVZ, LXC, and all that.

I heard snap is different abit than docker as it only focuses on applications